Contributor:

Cite as:

Vallejo, Arturo. 2019. "I, pajarero. A visual-autonarrative approach to citizen science." In "Methodological Interruptions Across the Field and Archive: Doing STS in Mexico", created by Arturo Vallejo. In Innovating STS Digital Exhibit, curated by Aalok Khandekar and Kim Fortun. Society for Social Studies of Science. August.

https://stsinfrastructures.org/content/i-pajarero-visual-autoethnographic-approach-citizen-science

Lists: a Visual Journal/Journey

Pajarero, pajarera: a working definition

The Difference Between Bird Watching and Birding

A Phenomenon on the Rise

Contribution of Citizen Science Towards International Biodiversity Monitoring

A Brief History of Bird-Watching in Mexico through the 20th Century and the First Years of the 21th

Science, public participation and the Barbarian Invasions

Locations for Birding in Mexico City

Birds of Mexico City - Naturalista

Bourdieu, the Teakable Photo & the Pajarero Ethos

I study the collaboration between amateurs and professional scientists in the production of scientific knowledge through citizen science programs. I take as a paradigm the practices of massive and collaborative observation of biodiversity in Mexico carried out by the communities of birders and their interaction with the digital platforms eBird and iNaturalist. My intention is to analyze the communities of users of these platforms based on their "modes of thought", as well as their observed behavior, and their relationship with the production of scientific knowledge in the contemporary context.

I work with users of both platforms, but also with the repositories, the digital databases that harvest their observations, and with the users who develop different scientific products from the data stored in them.

From the data generated by citizen science -from observations gathered by amateurs-, scientific articles are published, conservation decisions are made and other types of scientific works are carried out that allow us to increase our knowledge about ecological patterns and their processes, such as distribution and abundance of species, phenology and ecological variables such as primary and secondary productivity, among others. But bird monitoring also has a social value. Those who promote these initiatives choose birds as an object of study because they are relatively easy to observe, they are present in all types of habitats, expeditions to observe them are reasonably accessible and in addition, birds are usually symbolically associated with history, traditions and the aesthetics of each locality. For this reason, knowledge of biodiversity in general, and of birds in particular, is expected to foster knowledge of local environments and increase the sense of belonging of those who participate in these initiatives.

But despite the growing popularity of platforms such as eBird and iNaturalist, in Mexico, citizen science programs, and particularly those related to bird watching, are still in the process of being shaped. Around them different strategies are being developed both to consolidate them as legitimate sources of scientific information for the knowledge and conservation of biodiversity, and to intensify the recruitment of volunteer observers. These strategies aim to be inserted into established scientific practices - based on observation protocols and quality control systems, for example-, but also into social practices, such as recreational activities. For these reasons I consider that the observation and analysis of the operation of both platforms can inform about the new factors and new dynamics involved in the production of scientific knowledge in the current local and international technoscientific context and its integration into society.

My first contact with citizen science was in Raleigh, NC, during the annual meeting of the Association of Science-Technology Centers (ASTC). At that time, I worked in a museum in Mexico City and as Director of Content I had heard about this phenomenon, but I had never witnessed it in person. As someone who is professionally and emotionally related to science without being a professional scientist, I was attracted to the possibility that someone like me could participate in a formal research project.

At first I started as a participant observer, watching the birders as they scanned different urban and rural "natural" areas for specimens. I was, we could say, "watching the watchers" and I must confess that birds held little interest for me, in great part because I was utterly unable to identify any of them. However, during one fieldtrip I was encouraged to try some binoculars. This was an enlightening moment for me, because for the first time I was able to "see" a bird. It was then that I realized the importance that the process -the long and hard experiencial road a birder has to travel to develop the necessary skills (which can be characterized as contributory expertise) to locate and identify birds- has for the citizen science experience, for biodiversity monitoring and for the production of knowledge. It was then that I decided to shift the focus of my research from them, to me, to my own immersion and process. I became, then an observer participant.

I hope that my story is significant to citizen science in two ways. On the one hand, because although more and more papers and reports related to this type of initiatives are published, the majority come from the managers of the citizen science programs themselves; there are still few independent research projects and even less ones that come from a user. In this sense, one of my contributions is the application of qualitative methodologies to study the cultural practices of the pajareros (birders), their values, beliefs, languages, meanings and, in short, their ethos.

Autoethnography, autonarrative, autoresearch. The work of Carolyn Ellis has been very influentional to my own. To me, her approach represents the opportunity of going further than just mere reflexivity -something that already was an interest of mine- and delving into my own subjectivity, interests and affections. For instance, I am partial to citizen science and I know it. Rather than forcing a political and critical perspective to my research topic, going into an autonarrative mode frees me to explore the reasons for my partiality. It is, so to speak, an ultra-situated perspective.

With a background such as mine, in Film & Literature, I almost felt obligated to incorporate a visual and narrative approach to my reseearch. This is true, but it is much more than that: the pajarero, or birder, subculture, is very visual culture. Birders observe, they describe visually, they take photographs, some draw illustrations of birds, they use binoculars or spyglasses, they use illsutrated field guides. For this reason, the work of Sarah Pink and Dawn Mannay has provided me with a road map to conduct my own research.

Bonney, R. (1996). Citizen science: A Lab tradition. Living Bird, 14(4).

Bonney, R., Ballard, H., Jordan, R., McCalie, E., Phillips, T., Shirk, J., & Wilderman, C. C. (2009). Public Participation in Scientific Research: Defining the Field and Assessing Its Potential for Informal Science Education. A CAISE Inquiry Group Report. Washington, D.C.: Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education (CAISE).

Bonney, R., & Dickinson, J. L. (2012). Overview of Citizen Science. In J. L. Dickinson & R. Bonney (Eds.), Citizen Science: Public Participation in Environmental Research. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. “Towards a Sociology of Photography.” Visual Antopology Review 7 (1): 129–33.

Bucchi, M., & Neresini, F. (2008). Science and Public Participation. In Handbook of Science and Technology Studies (Third, pp. 449–471). Cambridge, Massachusetts, London,. England: The MIT Press.

Callon, M. (1999). The Role of Lay People in the Production and Dissemination of Scientific Knowledge. Science Technology Society, 1(4), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/097172189900400106

Chandler, M., See, L., Copas, K., Bonde, A. M. Z., López, B. C., Danielsen, F., … Turak, E. (2017). Contribution of citizen science towards international biodiversity monitoring. Biological Conservation, 213(Part B), 280–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.09.004

Collins, H. M., & Evans, R. (2009). Rethinking Expertise. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Daston, L. (2008). On Scientific Observation. Isis, 99, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1086/587535

Ellis, Carolyn. 2004. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Rowman Altamira.

Gómez de Silva, H., & Alvarado Reyes, E. (2010). Breve historia de la observación de aves en México en el siglo XX y principios del siglo XXI. Huitzil. Revista Mexicana de Ornitología, 11(1), 9–20.

Irwin, A. (1995). Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development. New York: Routledge.

Irwin, Aisling. 2018. “No PhDs Needed: How Citizen Science Is Transforming Research.” Nature 562 (October): 480–82. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07106-5.

Law, John, and Michael Lynch. 1988. “Lists, Field Guides, and the Descriptive Organization of Seeing: Birdwatching as An Exemplary Observational Activity.” Human Studies 11 (2/3 Representation in Scientific Practice): 271–303.

Mannay, Dawn. 2017. Métodos Visuales, Narrativos y Creativos En Investigación Cualitativa. Madrid: Narcea.

Pink, Sarah. 2007. Doing Visual Ethnography. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Piña Romero, J. (2017). Ciencia ciudadana como emprendimiento de la ciencia abierta: el riesgo del espectáculo de la producción y el acceso al dato. Hacia otra ciencia ciudadana | Ciência cidadã como empreendimento de ciência aberta: o risco da espetacularização da produção e o acesso ao dado. Para uma outra ciência cidadã | Citizen Science as an open science enterprise: the risk of a spectacle of production and the access to data. Towards another citizen science. Liinc em Revista, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.18617/liinc.v13i1.3765

Riesch, H., & Potter, C. (2014). Citizen science as seen by scientists: Methodological, epistemological and ethical dimensions. Public Understanding of Science, 23(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662513497324

Vallejo, A. 2016. “Ciencia, participación pública y las invasiones bárbaras.” Ludus Vitalis. XXIV (46): 205-208.

All Innovating STS exhibits are oriented by nine shared questions in order to generate comparative insight. These are:

ARTICULATION: What STS innovations (of theory, methodology, pedagogy...Read more

Furthering its theme, Innovations, Interruptions, Regenerations , the 2019 annual 4S meeting in New Orleans will include a special exhibit, Innovating STS , that showcases innovations ...Read more

I made this video using the "trailer" function of iMovie. It is meant to showcase some of the fieldwork I have made during my research while following several birders and birding collectives around Mexico City. I used a GoPro camera with a chest harness to recreate a P.O.V (Point Of View) shot/perspective of some sort.

According to the dictionary of Mexican terms, pajarero (masc.) or pajarera (fem.) refers to a person that for pure pleasure watches and identifies birds in their natural environment.

Diccionario breve de mexicanismos de Guido Gómez de Silva

As the character portrayed by Steve Martin in the film The Big Year reminds us, pajarero is not equated to the English term of "bird watcher", but to "birder".

"Birds are natural; birders aren’t." This article, by Johnathan Rosen, publised by The New Yorker in October 17, 2011, lays out the not-so-sutil distinction between people who like birds an people who make watching, identifying and registering birds their way of life, their mission, their quest.

This provocative title in an article published in Nature is meant to raise some eyebrows while it reflects on the fact that:

Projects that recruit the public are getting more ambitious and diverse, but the field faces some growing pains.

Nevertheless, it seems that -hey, hey, my, my- citizen science will never die. At least not any time soon.

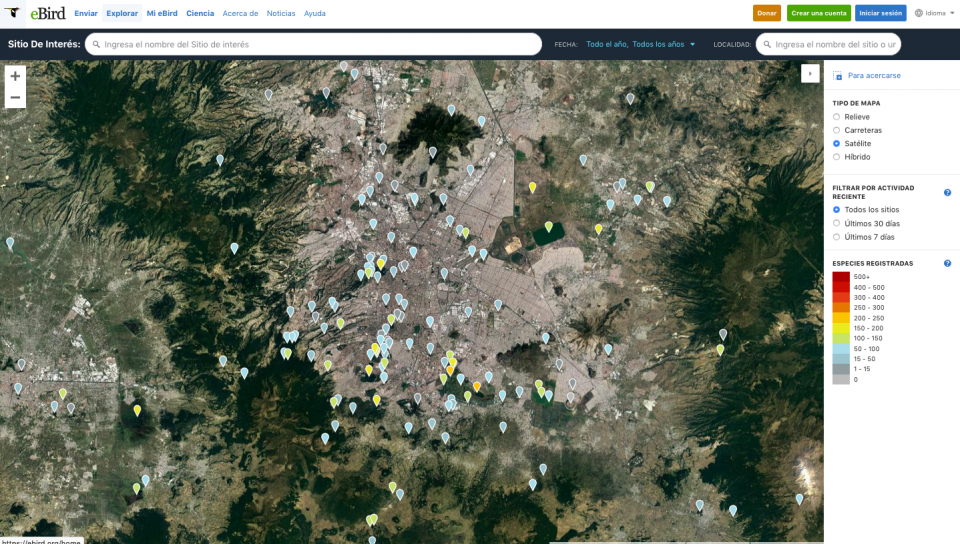

This research is motivated by two factors: 1) the rise of citizen participation and open data in scientific research, particularly in terms of biodiversity monitoring and in which bird watching has taken the lead and; 2) the renewed interest in Mexico towards ornithology. In our country, both factors have been stimulated in large part by the introduction of eBird and Naturalista, digital platforms that allow their users to record their observations, share them with other fans and also offer them information tools to improve their experience when performing this activity.

But in addition to offering a space to practice a hobby, both platforms serve as data sources to obtain information on the abundance and distribution of bird species. Both platforms are articulated with formal science structures as the observations recorded in them are also integrated into local databases, such as Enciclovida and the National Biodiversity Information System (SNIB), from where they are harvested by global repositories, such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Once there they are available to professional scientists (although they are open to anyone interested), who can use them for their research projects.

This is a classic essay from Lynch & Law that showcases birding, specially the elaboration of lists, as a literary and semiotic process.Read more

Another classical, this one at a local level. Gómez da Silva & Alvarado Reyes narrate the scarce story of bird watching in Mexico and its recent surge as a hobby to constantly growing communities of birders.Read more

This paper, published by the Ludus Vitalis journal, devoted to meta-scientific reflections was my first attempt to grasp the topic of citizen science. At it's core, citizen science harbors the question of public participation in science and its viability. Rather than asking if the...Read more

Riesch and Potter (2014) conducted a research study about the perception that professional scientists have regarding citizen science. A series of qualitative interviews showed that the main concerns were related to the methodological-epistemological and ethical aspects as potential obstacles to the development of the field. To sum up te results, these concerns are:

● The quality of the data was a quasi-universal concern among the respondents

● Regarding ethical angles, concerns were related to the open science and free access: if it is the public who is collecting data that is subsequently integrated into national and international databases and is being used in academic publications, it can be argued then that said public may claim ownership and co-authorship over said information

● Also on ethical aspects, some respondents agreed that it seemed necessary to reward the volunteers, given the time (leisure time) and effort dedicated to these projects

● An additional concern had to do with the level of commitment of the participants, because they dedicate their leisure time to these projects this type of projects has no way of ensuring timely and regular participation by the volunteers.

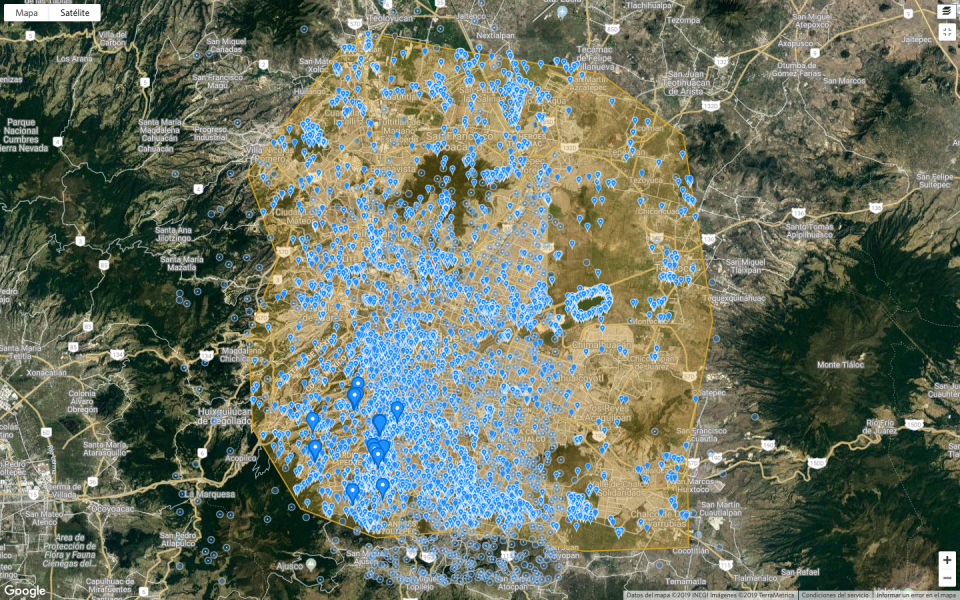

Where can birders perform their hobby in a place such as Mexico City? It can be anywhere really because birds can be seen on roofs, in fences or in lampposts. However, there are privileged locations, spaces that have been classified as "natural" within the urban area. Mexico's capital city today has 19 Natural Protected Areas (ANP) of which 8 are considered National Parks, and that in total total 20,924.95 hectares, 23% of the Conservation Land of Mexico City. To this territory we can add numerous parks and gardens, such as Chapultepec, San Juan de Aragón, Parque Hundido, Los Coyotes, Viveros de Coyoacán and Alamedas Norte, Sur, Oriente and Poniente. Most of the ANPs and natural areas are concentrated in the south of the City, a considerable part in the semi-rural districts, such as Xochimilco, Milpa Alta and Tláhuac. This regions have urbanized or semi-urbanized areas of considerable extension, both agricultural and forested, that they share with Estado de México and Morelos.

Satellite view with the polygon for the “Birds of Mexico City” project generated by the Naturalist portal in which bird observation records are shown. At the time of the publication the count was 36,461 records, with 417 species made by 1767 birders.

The interest towards citizen science has grown in recent years because it has appropiated an indispensable niche for current scientific research: the scale of the data, especially in research in ecology, as they allow information to be collected in a...Read more