Contributor:

Cite as:

García-Deister, Vivette. 2019. "Non-ethnography of San Fernando." In "Methodological Interruptions Across the Field and Archive: Doing STS in Mexico", created by Arturo Vallejo. In Innovating STS Digital Exhibit, curated by Aalok Khandekar and Kim Fortun. Society for Social Studies of Science. August.

https://stsinfrastructures.org/content/non-ethnography-san-fernando/essay

DNA Will Not Solve Mexico's Unidentified-Body Crisis

9.01.10 – 15:36/Exceeded Capacities

Zombie Invasion in a Country of Dead

Memorial in Mexico City for the 43 Students from Ayotzinapa

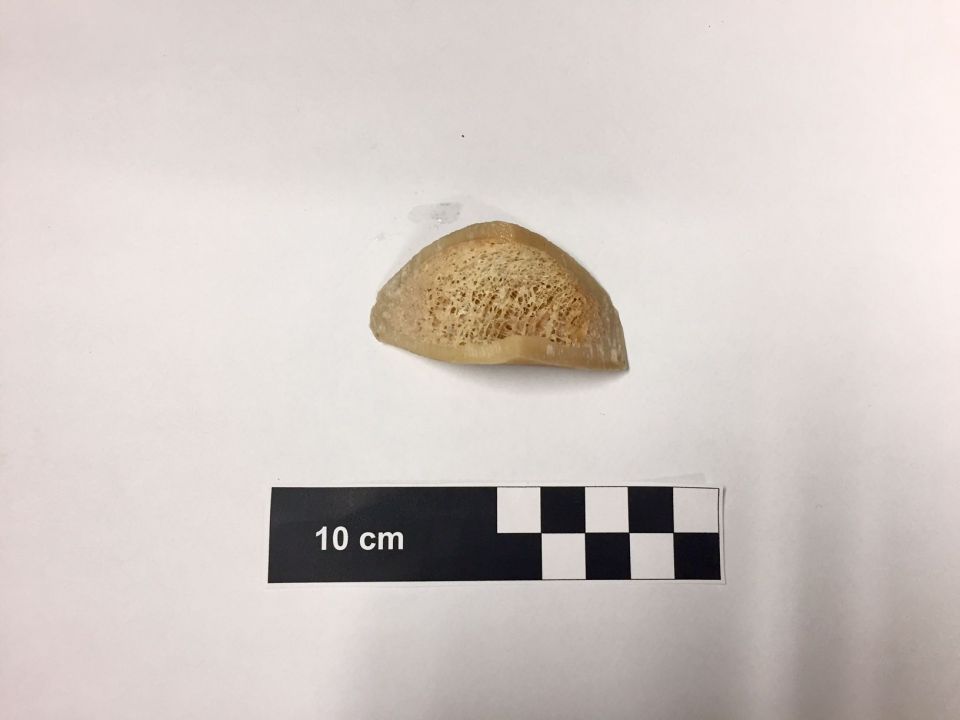

In August 2010, the dead bodies of 72 migrants (58 men and 14 women) were found in a ranch in San Fernando in the border state of Tamaulipas. Between April and May 2011, 193 more migrant remains were discovered in several clandestine mass graves in the same area. These incidents came to be known as the “San Fernando massacres”. Due to the high visibility of the case and to international critique regarding the Mexican government’s initial attempts to determine the identities of the migrants, which were marked by egregious errors, these efforts of identification became extremely reserved. The institutions and forensic teams working on this case were effectively inaccessible. Identification of these victims has also lasted longer than expected. By 2014, a special commission had been able to identify and repatriate 180 bodies. To this day, a few remains still await identification.

Despite San Fernando being a focal point for migrant death, to understand migrant identification and forensic capacities in Mexico I have had to work ethnographically around San Fernando. My lack of access to this case notwithstanding, the deadly presence of the San Fernando victims continues to crop up and delineate the contours of my field.

Writing about violence in her captivating essay “Dying Worlds”, Kamala Visweswaran introduces the term Fieldnoting:

In pressing the noun into a verb, … I am not after any narrative of possession or dispossession of the object writers who are not anthropologists might also refer to as “field notes”[…] Neither do I have in mind a tweeted or blogged version of “live fieldnoting” with daily entries of one to five sentences that some students are experimenting with, nor an intermediate form of writing between original field notes (to be recuperated as fetish object) and full analytic argument, but a form of writing that is ongoing and processual. Fieldnoting attempts to track its sources of mediations; it does not pretend to be separate from media and other circulations of reported speech or discourse that inevitably converge upon a “field.” Fieldnoting is the process through which the field itself—its scenes and analytics—is denoted or defined, tracked through a field of proliferating associations, but also a network of blockages and apprehensions. Any field, and our perception of it, shifts over time. It is both structured by the processes of accretion, sifting, and assemblage and attentive to those same processes (In: Orin Starn (ed.) 2015, Writing Culture and the Life of Anthropology, pp. 208-209).

I characterize a forensic happening as an event or situation that explicitly calls for a performance of forensic science. As violence in Mexico escalated and recourse to forensic science unfolded before my eyes —and at the same time my access to state laboratories and forensic teams was restricted—, fieldonting of forensic happenings became vital to my research methodology.

Brown, W. 2010. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty. Cambridge: Zone Books.

Cantú F. 2018. The Land Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border. New York: Riverhead Books.

De León J. 2015. The Land of Open Graves. Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fassin, D. 2011. Humanitarian Reason: A moral History of the Present. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Paley, D. 2014. Drug War Capitalism. Oakland: AK Press.

Povinelli, E. A. 2011. Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

All Innovating STS exhibits are oriented by nine shared questions in order to generate comparative insight. These are:

ARTICULATION: What STS innovations (of theory, methodology, pedagogy...Read more

Furthering its theme, Innovations, Interruptions, Regenerations , the 2019 annual 4S meeting in New Orleans will include a special exhibit, Innovating STS , that showcases innovations ...Read more

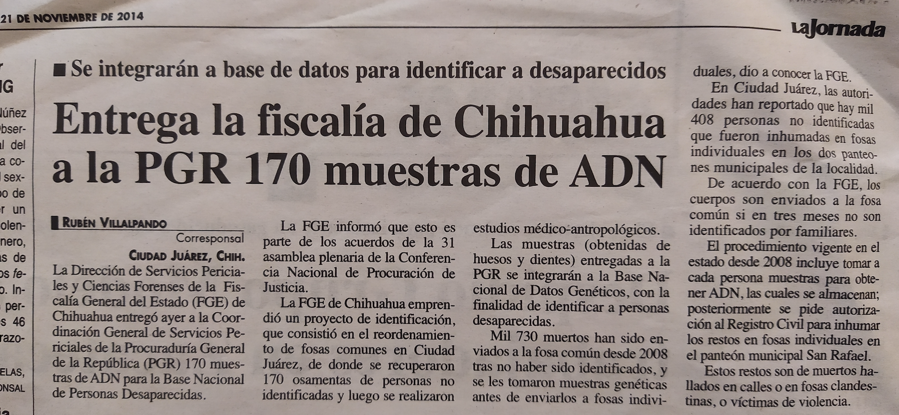

It was the year 2013. I was researching public engagement with biomedical genetics in Mexico when forensic genetics broke into the scene. I did not choose it as a research topic; forensic genetics became an object of study by necessity. To understand the relative lack of public engagement with biomedical genetics in Mexico I needed to understand the ever-increasing public engagement with forensic genetics. A research article that marks this moment in my investigation was published in SSS in 2015.

Part of this research has been supported by a Wenner Gren Foundation Collaborative Research Grant, and conducted in collaboration with Lindsay Smith.

http://www.wennergren.org/grantees/smith-lindsay-adams

Support form the Wenner Gren Foundation and UNAM Project PAPIIT IA401416 also made the following events possible:

In one event, a science café (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Café_Scientifique) held in May 2017, we engaged with the general public in Morelia, Michoacán, to jointly reflect on the role of forensic genetics in the context of death and disappearance in Mexico

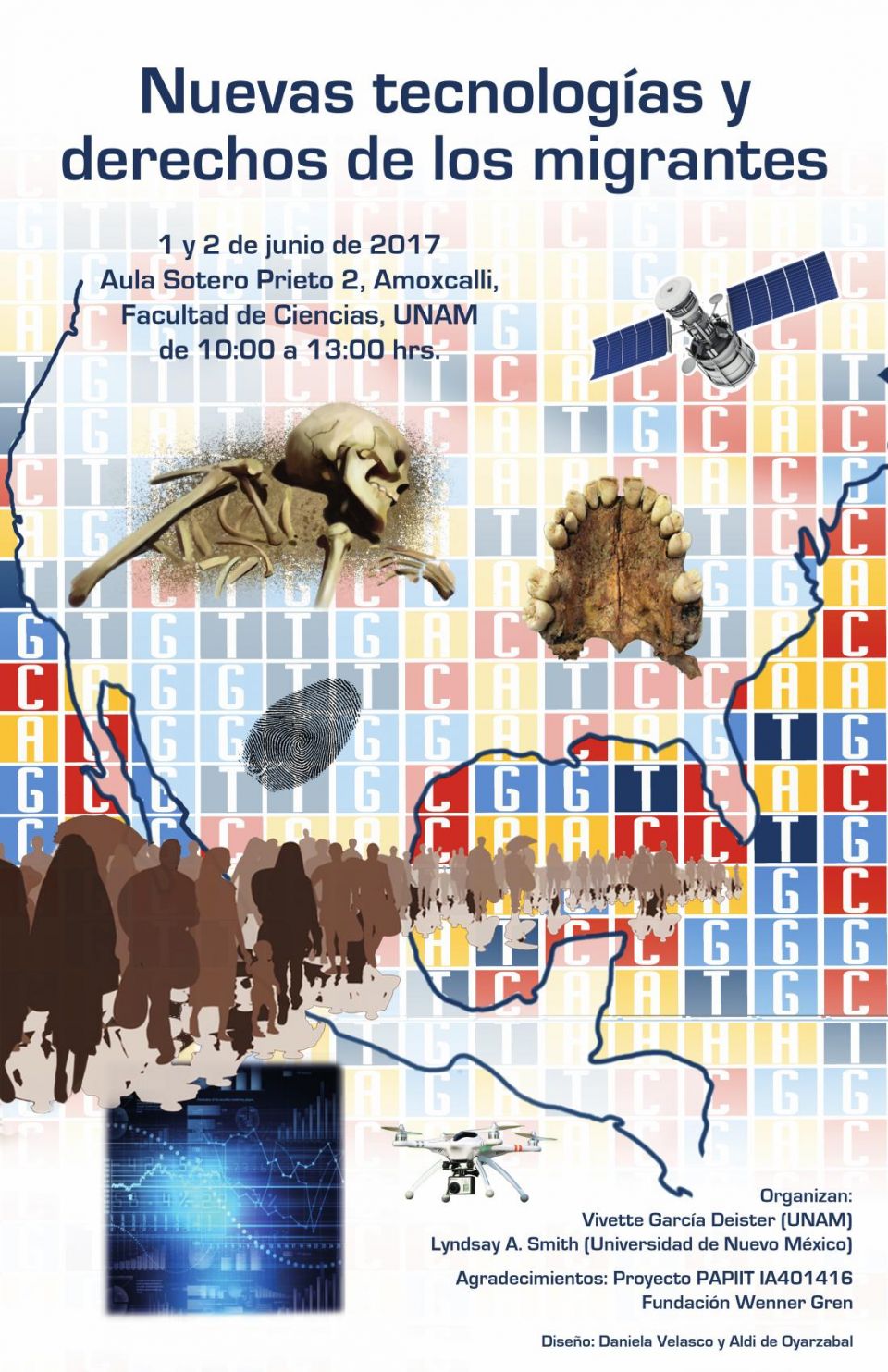

In a project workshop held at UNAM’s Faculty of Sciences in 2017, we engaged with activists, geneticists and NGO researchers to explore the intersections between the use of identification technologies and migrant rights.

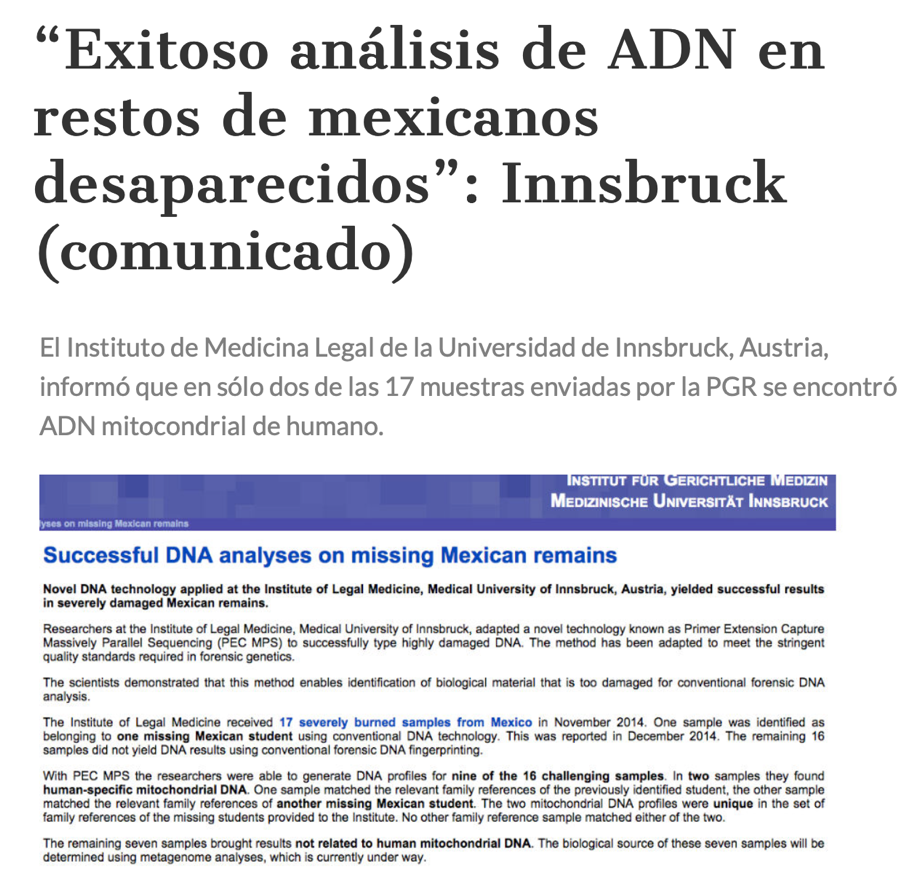

The forced and ethnically targeted disappearance of 43 students of the Escuela Normal Rural Raúl Isidro Burgos, from Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, in September of 2014 was the most visible human rights crisis of Enrique Peña Nieto’s presidential term. In response, the Mexican government worked (and failed) to assemble a forensic science capable of explaining their disappearance, and their alleged assassination and calcination by drug traffickers (García-Deister and Smith 2016). The investigation has been recently re-opened, and the radius of search for the students has been expanded.

FOTO: ACOSTA MARIO/FLICKR