The emergences of a community of practice by learning and working together needed a certain methodology to keep the group together. A rhythm of study was established in the weekly meetings in order to cultivate a sense of belonging and to boost the richness of interaction among the group members.

Reading, debating, systematizing, and licensing was the first method used by the community.

Publishing was the second.

In the process of building collaborative efforts a network of mentors and academic partners emerged from Argentina, Colombia, France, and the United States. Between 2008 to 2012 the STS study group enrolled scholars from different STS genealogies.

HERNÁN THOMAS

Technologies play a central role in the processes of social change. They demarcate actors’ positions and behaviors; condition social structures distribution, production costs, access to goods and services; generate social and environmental problems; and facilitate or hinder its resolution.

It is not a simple matter of technological determinism, neither a causal relationship dominated by social relations. Technologies are social constructions as much as societies are technological constructions.

However, the debate on the technology-poverty relationship has been scarcely tackled in Latin America. Beyond some developments applied in “appropriate” technologies, and the explanation of an ambiguous relationship between technology and economic and social development, few studies have focused on this problem.

Given the scope, scale, and depth of the problem of poverty in the region, the development of “social technologies” (understood as technologies aimed at solving social and / or environmental problems) is of key strategic importance for the future of Latin America. The inclusion of communities and social groups will probably depend on the local capacity to generate both adequate and effective productive technological solutions.

The idea of social technology was built upon previous debates about appropriate technology, and it was opposed to what was regarded as conventional technologies, namely those artifacts and innovations that were designed for maximising profit, assure control over production and limit social participation.

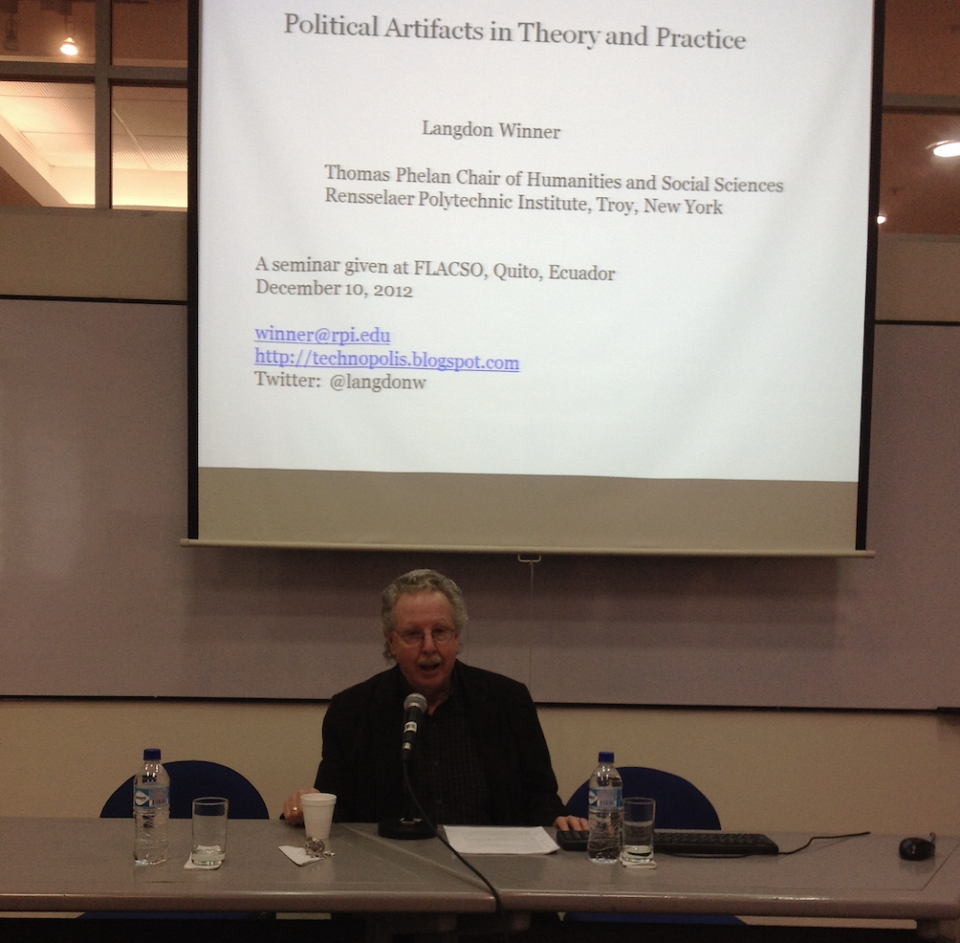

LANGDON WINNER

Langdon Winner's workshop in Quito referred to politics and political theory of “how to live together.” It involved political institutions, political practices, communities, human beings ever formed, and the ideas that inspired their efforts.

His approach to political artifacts tried to shed light on questions by looking at the presence of material things: technologies and pieces of architecture as they effect political life. Specifically, how the presence of certain technological structures have to do with how we understand community. How does it affect how we understand freedom, our understanding of justice, and power? How material things embody political life. The way material artifacts reflect the values of society and how they can change social relations and political power. So the crucial question is not how things are socially constructed or power configured in society. But rather, what do we mean to each other?

Winner focused on compatibility. What kind of technical patterns are compatible with different forms of political life.

ERNESTO LLERAS

Lleras understands a 'community' as a social group with the capability of sharing actions to achieve a purpose. Such community can be suggested to be a 'learning community' reinforced by its intention to promote the development of individual and collective abilities and mechanisms for designing new realities or transform the current conditions according to the expectations of the organization's members and the environmental requirements. This necessarily implies the emergence of explicit relationships between people based on one hand, cooperation, loyalty, and solidarity, and on the other hand, the dialogue and conversational permanent spaces as an active way for collective construction.

The concept of "learning community" has been developed as a methodology that connects to being-in-the-world with others, including the awareness of the perspectives of diverse actors and interests. Dialogue is central to this process and recognizes meaning and sense, through the process of observing relations. Observing relationships implies monitoring three main relational aspects: 1) power relationships; 2) communicative relationships; and 3) production relationships.

DOMINIQUE VINCK

Vinck’s workshop on network mobilization was based on Callon’s sociology of translation. When debating how mobilizing researchers also implied mobilizing public authorities by mechanisms of enrolment. Vinck showed how the various actors mutually defined one another by elaborating problematizations, by building means to solicit interest, and enrolling allies. Therefore, it is a myth that researchers live in an ivory tower secluded in a scientific community. On the contrary, researchers are moved by relations and activities that reach beyond the laboratory and their epistemic communities.

They operate in trans-epistemic arenas where they publish, procure funding, travel to meetings with industry, manage public research interventions and advise policy-makers. Due to this continue networking, researchers modify their proposals, redraft articles, continue or abandon enquiries according to industry’s response, with implications beyond the laboratory life. In other words, they articulate scientific and technological choices in the interest of specific social groups; thus scientific and technological choices is continuously negotiated.